- Home

- L. Ron Hubbard

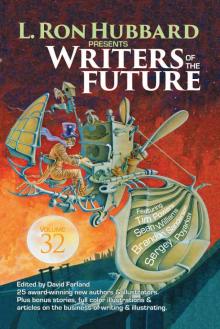

L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future Volume 35 Page 9

L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future Volume 35 Read online

Page 9

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR

Allen Morris was born in 1991 in the Mississippi Delta, growing up surrounded by endless horizons.

Long hours with books and role-playing games after school with friends solidified his love for exploring foreign worlds. Art, since a young age, would offer a different avenue to fulfill that explorative need through creation. He continues to travel and practice his craft daily. www.allenmorrisart.com

The Damned Voyage

APRIL 10

The Southampton docks were bedlam, people shouting and gawking, cursing and rushing. Beyond all this a stream of first-class passengers boarded. The ship would soon be underway, to where I neither knew nor cared. I needed to be aboard.

Gusts of warm, brisk wind forced their way around us, and I shifted more weight to the ever-present cane. To my right, Singh, companion and best friend for more than a quarter century, stepped closer to offer support. I took an equal step away, which was met by a resigned shrug. Singh never had understood stubborn English pride.

“It is here, Doctor Shaw,” he said.

It was. I’d felt the damned thing calling to me, insisting, as soon as we’d arrived. “Yes. It’s aboard the ship.”

The two thieves must have boarded earlier with the lower classes.

A brief sigh escaped me. This mad adventure was better suited to someone half my age. At sixty-one I should have been in front of a fire, penning memoirs no one could ever read. Memoirs of death, madness, and an ancient evil mankind was better off not being aware of.

Singh stepped into the crowd, one hand under his robe on the concealed dagger. Always ready. People took one glance at the massive Indian’s emotionless face and created a path while I followed in his wake.

The first-class passengers boarded in a steady stream across what was more wooden bridge than ship’s ramp. At the base of this bridge I plucked at Singh’s robe, stopping him from forcing his way to the deck above. He turned.

In 1878 I had helped rescue Singh from a final holdout sect of the Thuggee cult, a cult we had thought long broken, destroyed. Now, three decades later, no trace of that orphan boy remained, having become a man of solid muscle and determination.

And now I had to leave him.

“I’ll be taking this voyage alone, old friend.”

A flicker of anger passed over Singh’s face, arms crossed over thick chest. At six and a half feet, the man towered over me by almost a foot.

“You need to go to London,” I said, holding up one hand. “In case I fail.”

Singh’s expression didn’t change and I nodded my understanding. Aboard that ship were two men who had stolen an item he had vowed to keep safe, as he had vowed to keep me safe. Now I was asking him to abandon both.

Perhaps he understood English pride better than I thought.

“Go to the Prince’s son,” I continued. “His father knew the dangers of this book and so does he. Warn him it’s loose in the world again.”

Prince Albert Victor was dead now, as were most of the group that had come together in Whitechapel twenty-four years ago. They’d done their duty, retrieved the book and earned their rest, all except myself and Singh, of course, who were charged with keeping it out of the wrong hands, and Kosminski who would rave in an asylum until he died.

“He may be illegitimate,” I said, “but he will have the resources to help.”

“He will listen better to you.”

“Perhaps, but I couldn’t endure the carriage ride, much less handle the horses. I only made it here through your skills.”

I’d walked with a limp for more years than not and forgotten what it was like to not carry a cane. Getting about was not a problem, controlling a carriage would be. On top of this, the breakneck trip here had taken its toll, though I struggled not to show it.

“The book calls to you, Doctor,” Singh said. “Will you resist when it’s in your hands again?”

“My leg is lame, not my mind,” I snapped.

Missing last night’s sleep had made me irritable and short-tempered, and Singh’s blunt words were too close to the truth. The damned book did call to me, had called ever since I’d opened it and read those few words twenty-four years ago. We’d followed that calling over the space of miles, from Cambridge to here.

Would I be able to resist?

I closed my eyes and calmed my mind.

“You’ve taught me well, Singh. How to meditate and block the voices.”

Singh heaved a deep sigh, the only sign he would give of his frustrated resignation. He knew this was too important, that precautions needed to be taken.

“How will you get aboard?” Singh gestured toward the deck above.

Fair question. We’d had little money in the house, certainly not enough for a first-class ticket. I’d taken all we had, grabbing my doctor’s bag as an afterthought. There was one possibility as I saw it.

“Ships like these allow first-class passengers to have friends and family, even their doctors, go aboard to see them off.”

All these well-heeled passengers milled about, chattering their inane conversations, making sure not to give the appearance of being in line to board the ship. They were far too important to queue up.

Singh strolled the length of this line that was not a line, acting like one of many dock workers. The rich ignored him. Twenty passengers along Singh stopped, made a sharp about-face and headed back. Where he’d turned stood an elderly woman, some aging dowager, stooped and wrinkled, perhaps ten years my senior. She fanned herself against the unseasonal heat while waiting to move forward, alone.

“Best of luck, Doctor,” Singh said as he passed.

I headed for the woman.

Illustration by Allen Morris

“Good morning, madam. Archibald Shaw at your service.”

She started and glared around at this intrusion. I waited for my appearance as a plump older gentleman to register as unthreatening. My receding gray hair and squared lenses completed the image of a latter-day Ben Franklin. Her glance dropped to my doctor’s bag then back to my face, a smile cracking her features.

“Oh, Doctor. A pleasure.”

“The pleasure is mine,” I assured her. “This heat is quite unbearable, is it not?”

That was sufficient to get her going on a lengthy diatribe of problems, starting at her sore feet and working up, leaving out none of the aches and pains of age. I offered her an arm for support and we ascended the ramp side by side. It had been years since I’d practiced medicine, but I still recognized this lonely woman for the hypochondriac that she was. She would have a bagful of medications when what she needed most was someone to listen. I made sympathetic clucking noises and tut-tutted in all the right places, trying to identify the perfume she wore. L’heure Bleu?

In the course of the one-sided conversation, moving slowly up the ramp, I was able to discover the ship was headed for New York after a couple of brief stops.

Reaching the deck above we found no less than the captain waiting to greet us. My companion introduced herself as Mrs. Penelope Hooper, then the man held a hand toward me, a dubious expression on his face which was quite understandable. My style of dress hardly measured up to first-class standards.

“Captain Edward Smith, sir.”

“Doctor Archibald Shaw.”

The other man’s expression changed, the smile more genuine. Everyone trusted a doctor. He appeared ready to continue the conversation but a crowd had accumulated behind us in our slow journey here. These guests requiring the captain’s attention worked in my favour as too much scrutiny from this man wouldn’t do. We moved on.

On the docks below there was no sign of Singh, on his way back to London already. I was well and truly alone, a thought which both saddened and frightened me.

My new companion continued chattering on about her medical woes while I half-liste

ned, scanning the passengers around us until I saw one that would suit my purpose.

“I beg your pardon,” I said as Mrs. Hooper took a breath. “I’m afraid I see a patient of mine I must speak with. May I look in on you later?”

“Of course, Doctor,” she said with a smile.

The man ahead had about an inch height over my own five foot eight, but I beat him by ten pounds in weight. Other than that we were similar in build, and he seemed to be alone.

He would do.

Only the amount of passengers making their way through the halls slowed him, but it was enough to keep pace. I was able to catch up as he reached the door to his cabin.

“Excuse me,” I called.

He gave a jump and turned towards me, an annoyed expression on his face which quickly passed.

“My apologies, I didn’t mean to startle you. Ship’s doctor.”

“No harm done, Doctor. Can I help you?”

“A couple of routine questions if I may?”

“Oh, of course. Please come in,” he said opening the cabin door.

Everyone trusted a doctor. Of course it was easier if that doctor looked like someone’s grandfather.

Glancing left and right I followed the man inside, allowing the door to close behind me.

The cabin was decorated in mahogany panelling and furnished better than my house. A bed with nightstand, a heavy wardrobe, a sitting chair, and a table with two chairs for taking tea. This would be one of the smaller first-class cabins, still a most comfortable way to cross the Atlantic.

I placed my bag on the table.

“What can I do for you, Doctor? Not to be rude but I do still need to change.”

“Yes, of course,” I said, glancing over at the massive chest at the end of the bed. “You are travelling alone?”

“I am. On my way to New York for business.”

I gave my most disarming expression, recollecting the basics of doctoring, building the trust of the patient. “First time across the ocean?”

“Yes.” The man shrugged. “Travelling in style.”

He glanced at the clock sitting on a chair-side table. As his focus changed I drew the sword concealed inside my cane, thrusting it forward in one fluid motion. The blade pierced the man’s heart, a killing thrust.

He looked at the sword protruding from his chest, expression changing from surprise to rage.

“Fall, damn you,” I said, withdrawing the sword and stepping back.

Blood gushed from the wound, but not shooting out as it should have. Not the immediate killing stroke after all, but fatal nonetheless.

The dying man rushed at me, hands outstretched. We landed on the floor, him on top with hands closing on my throat, his blood squelching between us. My sword skittered across the cabin, stopping against the bed’s leg. Strength left his grip, but not quickly enough. My lungs burned with the need for air while my heart pounded an irregular, terrified throb in my ears. With each beat the world went more gray, moving toward black.

Singh, I’m sorry old friend. I failed.

It would be up to him now to find the book and keep it out of the wrong hands. God knows we’d tried to do that over the years, moving from place to place, keeping away from those searching.

The black deepened, then receded back to gray. The man’s grip on my throat relaxed, and I gasped. The world came back into focus and I pulled one rasping breath into a burning throat. For several minutes we lay on the floor, the dead man’s weight pinning me until I mustered sufficient strength to move. Rocking him back and forth I eventually rolled him to one side. With the weight off I was able to draw more air into my lungs.

“Damn.”

How had I missed the artery, the entire heart? But raising my hands, so unaccustomed to precision work now, I knew how.

I lay on my back a long time, exhausted and hurting, needing a rest but having so much to do. Using what strength there was left, I crawled to the sitting chair and pulled myself upward with the help of that heavy furniture. Halfway to standing, I slumped into the chair. My head leaned back and eyes closed even as I tried to get moving again.

Perhaps a few minutes rest then.

Bastard.

My eyes opened and I focussed on the dead man’s face. “That I am, my friend.”

You’re no friend of mine.

“Why don’t you cross over?” I muttered, the room fading.

Then everything slipped into the blackness of unconsciousness.

The door to the small room lay before me and on the other side was the next woman I would question. It was a vast conspiracy, a spider web of cheap, brazen women, weathered and beaten down by fate, ready to grasp anything to give meaning to their lives.

The last woman had given the address for Mary-Jane Kelly.

Nearby, hidden in an alley, Singh and the others waited, making sure I would not be disturbed.

When the door opened and I saw the young lady on the other side I almost lost my nerve. This was no old whore in her declining years. This woman was lovely.

“And who sent you then?” she asked in an Irish lilt.

“Annie.”

The lass started, blonde hair bouncing around her face. “Annie’s dead.”

“Yes, she is,” I responded, stepping forward.

Mary-Jane Kelly did not die easily. It took hours for her to convince me that she was not part of the cult.

By then her death was a mercy.

My eyes snapped open.

I was cold and clammy with the sweat of nightmares, my body still thrashing against the soft upholstery of the reading chair.

Nightmares.

I hadn’t medicated before napping and those damned dreams, those memories, had taken me by force.

Aches and pains echoed through my body, unaccustomed as the muscles were to such strenuous work and of sleeping in a chair.

My glance drifted to the clock beside me.

“8:30?”

I bolted to my feet, all aches forgotten. It had been a few minutes before noon when we’d entered the cabin.

“No! I’ve slept more than eight hours.”

In that time the ship had not only launched but had come and gone from its first port in France.

You sleep well, for a murderer.

“You don’t understand,” I said, looking at the dead man’s body. “The thieves could have disembarked in France. I would never catch them now.”

I stood still, listening for the presence of the book.

“It’s still here,” I said.

Of course it was still aboard, the nightmare alone should have told me that much. Without the book’s presence I would have had a peaceful sleep.

Twenty-four years ago, when I’d brought the book home from Whitechapel, I succumbed to curiosity. I opened it, read from it. The first word threw me into convulsions. I read on, unable to stop. Another word. A full sentence. The words leaping from my mouth in lunatic screams.

Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn.

Singh had batted the book from my grasping fingers and I collapsed, spending the next weeks raving about ancient evils that no human mind should try to comprehend.

Those words still echoed inside my mind.

I tried to strangle you while you slept. The voice was hateful. I couldn’t touch you.

“Of course you couldn’t. You’re dead. All you can do is observe.”

The angry spirit gave a long mournful groan.

Using the furniture for balance, I made my way across the cabin to retrieve both sword and cane, then headed for the dead man. I wiped the sword against his chest.

My favourite jacket.

“You’ve no use for it now.”

The front of the man’s jacket, like the shirt underneath, was a mess of sticky b

lood. An inside pocket held a billfold which in turn held his ticket for this voyage. Both had been narrowly missed by the sword thrust. I pocketed the billfold after wiping it against the man’s jacket, and opened the ticket.

Bastard, the voice said.

“So you’ve said and I didn’t deny it,” I read the name on the ticket. “Stephen?”

I will kill you.

“No, you won’t. You can’t even touch me.”

You’re a monster.

“Perhaps.”

Stephen was silent a moment before replying in a low whisper. Why me?

“Convenience. I needed a cabin, ticket and clothes. You were close enough in height and weight.”

You killed me for my luggage?

I felt no desire to explain to this spirit, but if it would give him the closure he needed to move on … “No. I killed you to stay aboard this ship, and I would kill a hundred more like you to get this book back.”

Stephen sobbed and I wondered at a ghost’s ability to cry but left it.

There were some unavoidable tasks before I could leave the cabin to start my search. The sleep had done wonders and I found myself full of energy, though also full of aches and pains. Heading for the trunk, I flipped the lid up, throwing contents onto the bed.

Not enough to have murdered me? Now you vandalize my belongings?

I didn’t reply, continuing until the trunk was empty. Now it was light enough to be dragged across the cabin, my left leg giving complaint but I’d lived with that pain enough years to ignore it. Once it rested next to Stephen’s body, I tipped the trunk onto its back and opened the lid, then getting onto the floor next to the dead man, I used my good leg as a brace and rolled him inside. Rigors had set in, giving trouble with the bending of limbs, but there was no need to be gentle about it. In the end Stephen fit inside his own trunk.

Fifty-Fifty O'Brien

Fifty-Fifty O'Brien Villainy Victorious

Villainy Victorious Spy Killer

Spy Killer Ai! Pedrito!: When Intelligence Goes Wrong

Ai! Pedrito!: When Intelligence Goes Wrong The Dangerous Dimension

The Dangerous Dimension Mission Earth Volume 1: The Invaders Plan

Mission Earth Volume 1: The Invaders Plan The Slickers

The Slickers If I Were You

If I Were You The Doomed Planet

The Doomed Planet Writers of the Future Volume 31

Writers of the Future Volume 31 Mission Earth Volume 2: Black Genesis

Mission Earth Volume 2: Black Genesis Writers of the Future: 29

Writers of the Future: 29 Death Quest

Death Quest The Enemy Within

The Enemy Within Orders Is Orders

Orders Is Orders Hell's Legionnaire

Hell's Legionnaire L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future 34

L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future 34 The Scifi & Fantasy Collection

The Scifi & Fantasy Collection Dead Men Kill

Dead Men Kill Ole Doc Methuselah: The Intergalactic Adventures of the Soldier of Light

Ole Doc Methuselah: The Intergalactic Adventures of the Soldier of Light Shadows From Boot Hill

Shadows From Boot Hill Hurricane

Hurricane Mission Earth Volume 3: The Enemy Within

Mission Earth Volume 3: The Enemy Within Slaves of Sleep & the Masters of Sleep

Slaves of Sleep & the Masters of Sleep One Was Stubborn

One Was Stubborn Final Blackout: A Futuristic War Novel

Final Blackout: A Futuristic War Novel Devil's Manhunt

Devil's Manhunt A Matter of Matter

A Matter of Matter Voyage of Vengeance

Voyage of Vengeance If I Were You (Science Fiction & Fantasy Short Stories Collection)

If I Were You (Science Fiction & Fantasy Short Stories Collection) L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future Volume 35

L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future Volume 35 Mission Earth Volume 4: An Alien Affair

Mission Earth Volume 4: An Alien Affair Black Genesis

Black Genesis Tinhorn's Daughter

Tinhorn's Daughter Trouble on His Wings

Trouble on His Wings Writers of the Future Volume 27: The Best New Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year

Writers of the Future Volume 27: The Best New Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year Writers of the Future Volume 28: The Best New Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year

Writers of the Future Volume 28: The Best New Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year An Alien Affair

An Alien Affair Cargo of Coffins

Cargo of Coffins Mission Earth Volume 5: Fortune of Fear

Mission Earth Volume 5: Fortune of Fear Writers of the Future 32 Science Fiction & Fantasy Anthology

Writers of the Future 32 Science Fiction & Fantasy Anthology The Baron of Coyote River

The Baron of Coyote River Hurricane (Stories From the Golden Age)

Hurricane (Stories From the Golden Age) Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health

Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health Writers of the Future, Volume 30

Writers of the Future, Volume 30 Battlefield Earth: A Saga of the Year 3000

Battlefield Earth: A Saga of the Year 3000 Fear

Fear Disaster

Disaster Invaders Plan, The: Mission Earth Volume 1

Invaders Plan, The: Mission Earth Volume 1 A Matter of Matter (Stories from the Golden Age)

A Matter of Matter (Stories from the Golden Age) Writers of the Future Volume 34

Writers of the Future Volume 34 Death Waits at Sundown

Death Waits at Sundown One Was Stubbron

One Was Stubbron If I Were You (Stories from the Golden Age)

If I Were You (Stories from the Golden Age) Writers of the Future 32 Science Fiction & Fantasy Anthology (L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future)

Writers of the Future 32 Science Fiction & Fantasy Anthology (L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future) Writers of the Future, Volume 29

Writers of the Future, Volume 29 Mission Earth Volume 8: Disaster

Mission Earth Volume 8: Disaster Mission Earth 6: Death Quest

Mission Earth 6: Death Quest Writers of the Future, Volume 27

Writers of the Future, Volume 27 Mission Earth Volume 7: Voyage of Vengeance

Mission Earth Volume 7: Voyage of Vengeance Ole Doc Methuselah

Ole Doc Methuselah Mission Earth 07: Voyage of Vengeance

Mission Earth 07: Voyage of Vengeance Battlefield Earth

Battlefield Earth Fortune of Fear

Fortune of Fear Mission Earth 8: Disaster

Mission Earth 8: Disaster Mission Earth Volume 10: The Doomed Planet

Mission Earth Volume 10: The Doomed Planet Writers of the Future, Volume 28

Writers of the Future, Volume 28 Mission Earth Volume 6: Death Quest

Mission Earth Volume 6: Death Quest Dead Men Kill (Stories from the Golden Age)

Dead Men Kill (Stories from the Golden Age) Mission Earth 4: An Alien Affair

Mission Earth 4: An Alien Affair Spy Killer (Stories from the Golden Age)

Spy Killer (Stories from the Golden Age) Mission Earth Volume 9: Villainy Victorious

Mission Earth Volume 9: Villainy Victorious L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future, Volume 33

L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future, Volume 33